Beyond Work

Outside of architectural practice, my pursuits follow the same habits of observation, system-building, and visual reasoning that shape my design work. Whether diagramming a complex novel or mapping the growth cycles of carnivorous plants, I’m drawn to intricate systems and the challenge of making them visible. I do this in notebooks, sketches, spreadsheets, field journals…whatever fits.

These aren’t side interests so much as parallel practices. I share them with my wife and daughter, with friends, and sometimes with students.

My hope is to keep designing for resilience, clarity, and context… at home, at work, and wherever else the lines lead.

The Books I Return To

Reading is an essential part of my life. Nabokov famously said, "One does not read a book: one can only reread it." And that makes sense to me as I mine new understanding from each reading. Come to think of it, Nabokov should be on this list, too.

-

I reread V. to trace the boundary where technology disfigures life. It’s about what’s lost when the “animate” is pulled toward the “inanimate” (as Pynchon refers to life vs technology). It’s a haunting vision (reminder?) of progress as entropy.

-

This reminds me that attention is everything. It’s a meditation on boredom, discipline, and the costs of obsession… and how quiet effort might actually be heroic. At least I sure hope it is sometimes…

-

This is the book I read when I want to remember that human perception is insufficient. And that materialism especially is insufficient. It’s a dream logic meditation on futility and transcendence. The first book that felt addressed to me, personally.

-

I reread this for its controlled chaos. It’s a study in systems, power, and the illusion of free will. It questions whether everything is connected or nothing is (paranoia vs anti-paranoia as he sometimes puts it)… something I think about a lot.

-

This is the reminder that one perspective is never enough. It’s a layered view of obsession, failure, and our doomed efforts to control what we can’t even fully perceive. I might just have a tattoo of a Ecuadorian gold doubloon… if you know, you know.

-

I reread Suttree for the language. It’s an aesthetic experience unmatched even by others on this list. Beneath its drift through loss, poverty, and detachment is an atheistic vision of the world: indifferent, unadorned, and often absurd. Funny as hell, too.

-

I reread this as a psychological case study in how intellect and isolation can curdle into something toxic. It’s an unsettling portrait of self-justification, resentment, and the slow construction of a closed system of thought — and a reminder that inner architecture matters as much as outer.

-

Because everything is addictive, and the structures that pretend to connect us often isolate us instead. A bit depressing, I know, but resonant.

-

A book about mapping the world and dividing it — and how that urge both defines and damages American culture. It’s funny, tragic, and endlessly smart. Pynchon’s best characters are found here as I tend to agree his characters in other works are just personified concepts.

-

I come back to this because its the best informal case study of architecture in some ways. Also for its core question: how do we map the interior? It’s a book about a house that makes no sense, and about the psychological architecture we build to contain what can’t be measured. There’s something raw about fear, grief, and spatial unease here. Yes, the spatial unease is fascinating here.

-

I reread this for how it strips away the veneer of civilization. It’s a descent into the machinery of colonialism where language, commerce, and morality collapse under the pressure of exploitation. Its power lies in how little it resolves, and how much it expose. So… bedtime reading.

-

I reread this for how it fractures and refracts perspective (a theme in my fav books). Each voice distorts time, memory, and meaning in its own way, revealing how much can be lost or misunderstood depending on who's speaking. It’s a book that demands rereading just to begin hearing what wasn’t said the first time.

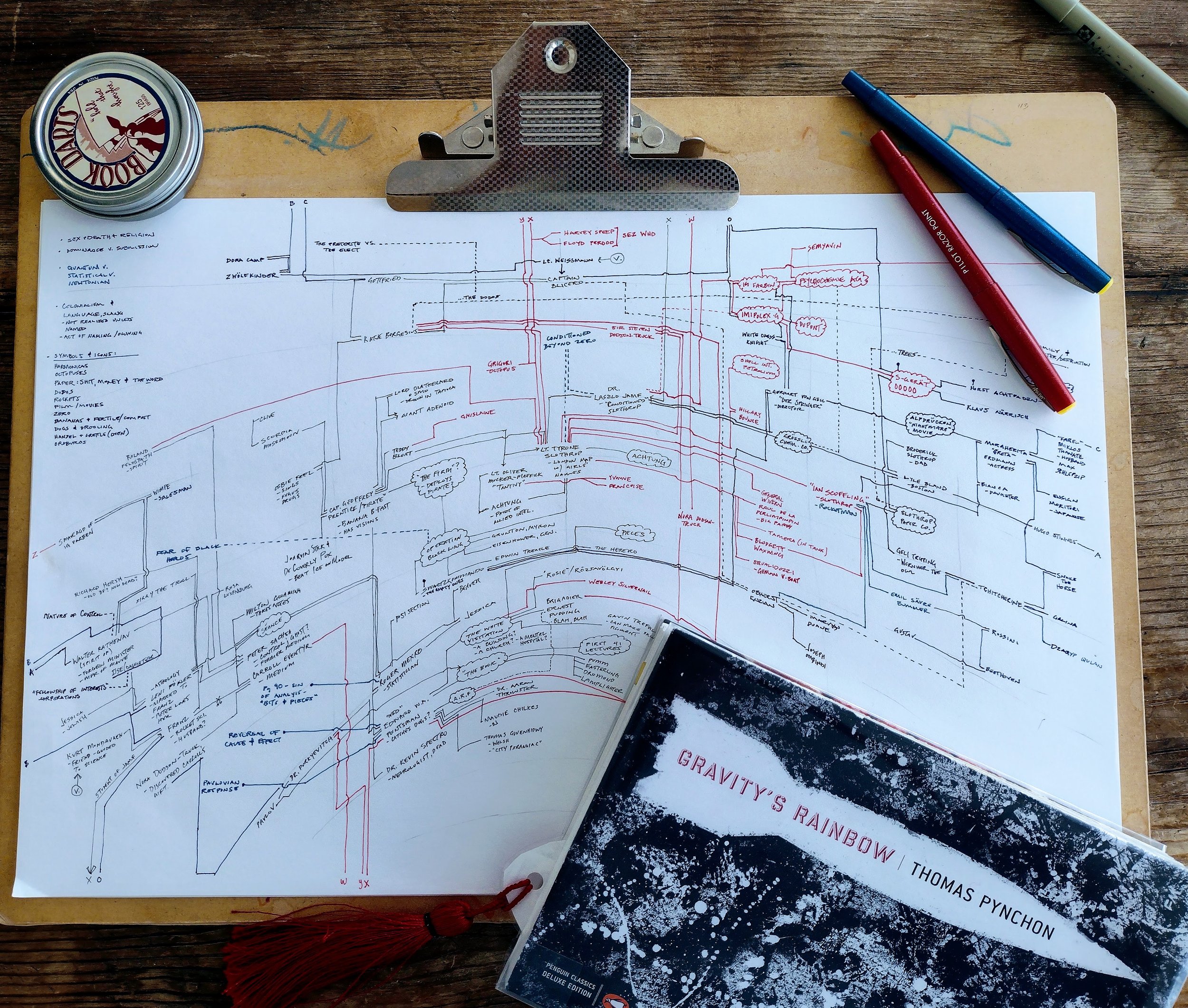

Literary Diagrams

Some novels I read with a pencil in hand and a sketchpad nearby. Especially with structurally complex or polyphonic works, I often find myself charting timelines, mapping relationships, or diagramming how a book moves. It's not always about clarity—sometimes it’s about seeing the shape of ambiguity, the architecture of narrative.

I’ve diagrammed Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, Gaddis’ JR, and Tolstoy’s War and Peace, among others. These diagrams are a kind of slow reading—a way to make visible the machinery underneath the voice. I’m less interested in decoding a text than in understanding how it holds together. This, too, is a design question.

My First Studio: Carnivorous Plants

Long before I became an architect, I wanted to be a botanist. Specifically, I wanted to understand and raise carnivorous plants. My obsession started in childhood before the internet made such a thing easy to research and it taught me how to teach myself: empirical observation, patient failure, and the dusty bliss of interlibrary loan. Add to that mix being in rural Alaska, mid 1990s.

Over more than three decades, I’ve raised, propagated, and hybridized dozens of species: Nepenthes, Drosera, Heliamphora, Dionaea, Darlingtonia, and especially Cephalotus follicularis. I maintained invitro propagation setups in closets and cabinets across various states and jobs, refining techniques that often felt more like alchemy than science. My propagation logs of failed tissue culture attempts and exacting substrate recipes taught me more about attention and iteration than most formal education ever did.

I specialized in cultivating Cephalotus, a species whose appeal never faded for me. At its height, my collection included over two dozen genetically distinct plants, many sourced from legacy growers in Australia. I’ve lectured about these plants in venues ranging from kindergarten classrooms to university ecology courses. Since the 1990s, I've been an active member of the International Carnivorous Plant Society (ICPS), subscribing to its research publication and exchanging material with other growers around the world.

<- I made this diagram of my Ceph Tank in answer to “How do you grow these difficult plants?”

In 2011, I joined a scientific expedition to Venezuela’s Mount Roraima. Afterward I contributed technical illustrations to the monograph Sarraceniaceae of South America. That work focused on several newly described Heliamphora species, including:

Heliamphora arenicola, H. ceracea, H. collina, H. minor var. pilosa, H. parva,& H. purpurascens.

Mount Roraima sits in my memory like a sealed terrarium: humid, harsh, and full of wonder. I stopped growing most of my collection when I became a father, but the love for these plants never went dormant. I’ll return to them one day. For now, I keep the notes, the photos, and the habits they taught me.

<- Nepenthes hamata & Cephalotus follicularis, the prizes of my once massive collection.

My Technical Illustrations